Of Epic Proportions

The bond between epic poetry and cinema is an old one – where heroes and villains, action and death, love and longing, spirit and body reside on paper and on screen with a magnificence that adapts to any language, giving you an experience that is always larger than life

Anu Majumdar

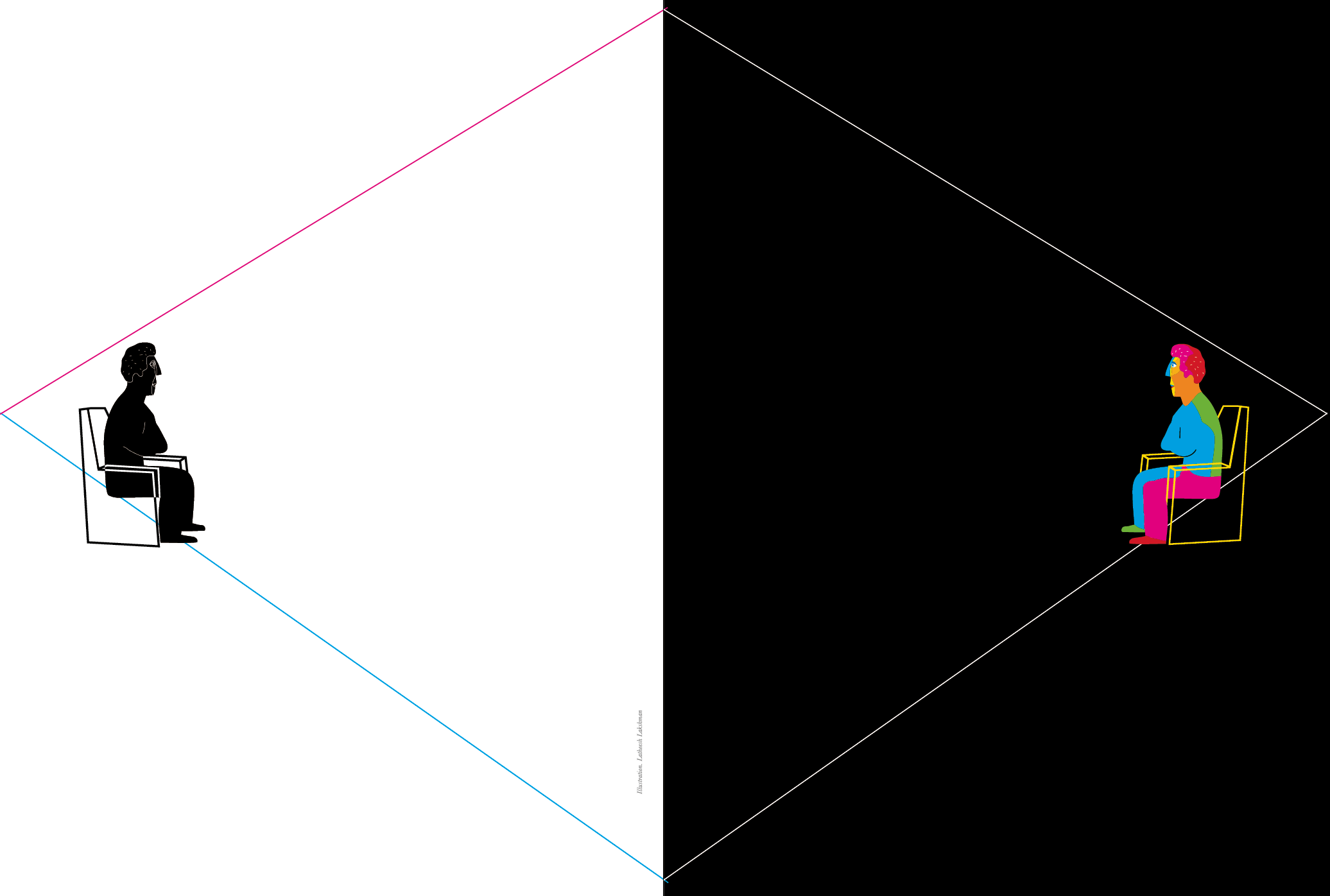

Perhaps it is the scale: a huge screen fills with images and voices, the sound of the sea and wind as enemies tramp across fields and one plunges through the darkness into a visual arena of action, complete with drama, love and strife, which makes film a natural extension of epic poetry.

An epic is a poem of some great length, which usually tells a story. In ancient times it was an oral form supported by a strong rhythmic metre, like Homer’s dactylic hexameter, instilling the cultural memory with tales of great kingdoms and heroes, some born of men, some of gods, the battles they fought, the journeys they undertook and of gods who protected or tricked them. These stories have seeped down to us through the centuries. Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid, Vyasa’s Mahabharata or Valmiki’s Ramayana continue to add meaning or bring fresh interpretation to the life we find around us.

Homer, the ancient Greek poet, was blind, but his ability to see the field of existence from man to the universe, is immortal.

Men are haunted by the vastness of eternity and so we ask ourselves, will our actions echo across the centuries? Will strangers hear our names long after we are gone and wonder who we were? How bravely we fought, how fiercely we loved…

The voice of Odysseus opens Troy, a Hollywood blockbuster loosely ‘inspired’ by Homer’s Iliad. That this film about the siege of Troy was released during the Iraq War, in the months that led up to the siege of Fallujah in 2004, was perhaps no coincidence. This is the greatest war the world has ever seen. But was it? It is not surprising, therefore, that critics were not always favourable. Mythological facts were thrown aside and heroes died or were killed at random to suit the plot and the epic sense reduced to an action film. Still, there are lines reminiscent of Homer that leap out of Troy: Nothing unites people like a common enemy, or that War is young men dying and old men talking. Or, Achilles’ wrath against an unjustified war and king, even as Odysseus entreats him to fight: Men are wretched things… Yet, a Greek hero’s business was to fight, to achieve kleos, an immortal glory, which could carry them past death to immortality.

If they ever tell my story, Odysseus says in the end, let them say I walked with giants. Men rise and fall like winter wheat, but these names will never die. Let them say I lived in the time of Hector…in the time of Achilles.

Heroes battling demons and enemies, good battling evil were salient features right from the epics of Gilgamesh and Beowulf, all heady stuff for the silver screen. The later more religious epics like Dante’s Divine Comedy or Milton’s Paradise Lost, full of moral trial and retribution, were not so easily cast on screen

Vyasa’s Mahabharata composed around the same time as Homer’s epics, is said to be the longest known epic poem, roughly ‘ten times the size of the Iliad and Odyssey combined,’ consisting of a 100,000 shlokas or couplets that spawn stories, histories and many adjacent tales through its 18 books. These have led to many film adaptations in India and around the world. Of them, the most renowned is Peter Brook’s film, The Mahabharata, possibly because it comes closest to a symbolic rendering of the myth.

Originally adapted for the stage without technical or virtual back-up, Brook invented a series of successful visual metaphors and symbolic settings that gave the film unusual power and integrity despite its stark beauty. We see a line of fire transcend distance allowing Duryodhana to see Arjuna’s actions far away in the Himalayas. But the film falls short of rasa, that taste of a knowledge-experience beyond the mental plane, so central when it comes to characters like Krishna or Bhishma.

The Mahabharata alters many definitions, especially that of the hero, the enemy and of immortality. Here Immortals are those who have conquered desire and grown one with divine knowledge, mostly great sages and, occasionally, warriors like Arjuna, who earned the knowledge of the Gita on the battlefield.

Ironically, the message of ahimsa or non-violence pervades the epic: ahimsa paramo dharma – non-violence is the highest law. It is there in the Book of Beginnings, in the Book of the Forest and, again, in the Book of Instructions, making Arjuna’s confusion on the battle field real:

What is kingdom to us, O Govinda, what enjoyment, what even life?

Those for whose sake we desire kingdom, enjoyments and pleasures, stand here in battle…

What pleasures can be ours after killing the sons of Dhritarashtra?

The Bhagvad Gita sees Krishna take him through the stages of yoga to a detached understanding of action while exhorting him to ‘stand up and fight.’ But it is not a fight for glory. Krishna counsels against all egoism or desire, the two greatest enemies.

Abandon all dharmas and take refuge in me alone.

I will free you from all sin and evil, do not grieve

Yet, after the long denouement of exile and war, of betrayals, intrigues and revenge, and many, many deaths, we arrive at last at the final scene. As people take leave of their loved ones in the battlefield, Gandhari enters and heaps a fresh curse on Krishna. It is a curse that perpetuates the cycle of war and revenge, the clash of prejudices and hierarchies even today. If that story changes, can civilisation alter?

Dadasaheb Phalke, the father of Indian Cinema, drew stories from the Mahabharata. In 1914 he produced his second film, Satyavan Savitri, a tale of conjugal love picked from the Book of the Forest. This tale also gave rise to a modern epic, Savitri by Sri Aurobindo. Written in English, the epic consists of 12 books with approximately 24,000 lines of blank verse, in iambic pentameter. The modern Indian literary milieu, impatient to leave the past behind, dismissed Savitri for its apparent mysticism, even denounced it as ‘a confused, unconscious parody of the worst features of English rhetorical style’. Yet, almost 70 years on, Savitri continues to be read across a vast cross-section of people throughout the world, remains continuously in print, and will remain so, one suspects, for a long time to come.

At a time when democracies have replaced kingdoms and war threatens to go nuclear and is remote-controlled, what use are heroes like Achilles or Arjuna? What is immortality while death and ignorance prevail over everything? A scholar of the Western Classics at Cambridge, who later translated and wrote on the Vedas and much of the epics, Sri Aurobindo took up the simple tale of conjugal love that overcomes death and moved it higher.

In the old epic, the childless King Ashwapati prays for sons for 18 years and is, in the end rewarded with a single daughter. Sri Aurobindo turns those 18 years into a spiritual journey, first by grounding Ashwapati’s individual realisation.

He drew the energies that transmute an age…

And cast his deeds like bronze to front the years.

His walk through Time outstripped the human stride.

Lonely his days and splendid like the sun’s.

This yoga would bring about a profound change in him:

A Will, a hope immense now seized his heart…

Aspiring to bring down a greater world

Ashwapati journeys further, traversing the world’s night, its dire ignorance and violent falsehood:

A greater darkness waited, a worse reign…He met with his bare spirit, naked Hell.

But there is no clang of armour here, no battle cry, for this battlefield is crossed with the spirit: A prayer upon his lips and the great name.

Ashwapati no longer seeks just another child but a greater birth: a power to change the future of the world:

Let a great word be spoken from the heights

And one great act unlock the doors of Fate.

He is finally granted a boon, a daughter, born to save.

One shall descend and break the iron Law,

Change nature’s doom by the lone spirit’s power.

With Savitri, Sri Aurobindo created a new kind of hero and a new kind of woman. Her strength is spiritual, calm and independent. Not given to weeping or helpless lament, Savitri makes her choices, some quite unorthodox, knowingly. She follows Death without fear, not to seek immortal realms with her beloved but to rescue Love and bring it back, to transmute the world’s pain and divisions.

My will is greater than thy law, O Death,

My love is greater than the bonds of Fate…

I am a deputy of the aspiring world,

My spirit’s liberty I ask for all.

With the spirit’s liberty there are now such things as a postmodernist epic. Named after Homer, Derek Walcott’s Omeros is composed in the three-line form similar to the terrza rima of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Set in Santa Lucia, in the Caribbean, Helen is a black housemaid in Omeros, sought after by two fishermen, Achille and Hector. But there are no gruesome tragedies here. Hector smashes his van for speeding. Then, there is Ma Kilman with the oldest bar in the village and special healing powers, and the Plunketts, left to come to terms with the British colonial past of the islands. The Greek myth serves as a means to express the truth of human relations and the past. Sergeant Major Plunkett travels back in time to relive some of his history. Achille journeys to Africa to find his father, his original name lost in the slave trade. And, most unusually, the poet himself speaks as he travels the world examining identity, the ruptures in his life and a racism that still wounds. And, finally, as he is about to lose all faith, he seeks out the blind guide, Omeros. This is a work of great beauty, carried by a deep love of the island and the sea and there is no need for heroes.

once Achille had questioned his name and its origin,

She touched both worlds with her rainbow, this frail dancer

leaping the breakers, this dart of the meridian.

She could loop the stars with a fishline, she tired

porpoises, she circled epochs with her outstretched span;

she gave a straight answer when one was required…

messenger, her speed outdarted Memory.

She was the swift that he had seen in the cedars

in the foam of clouds, when she had shot across

the blue ridges of the waves to a god’s orders,

and he, at the beck of her beak, watched the bird hum

the whipping Atlantic, and felt he was headed home.

Share