First, there was the Word

Five years ago, we visited artist Navjot Altaf’s studios that are a powerful mix of ideas finding resonance in an artist absorbing them like a sponge and giving us artworks that ask difficult questions, forcing us to look for answers within. In these times of social distancing, we revisit her studio through words.

Manoj Nair

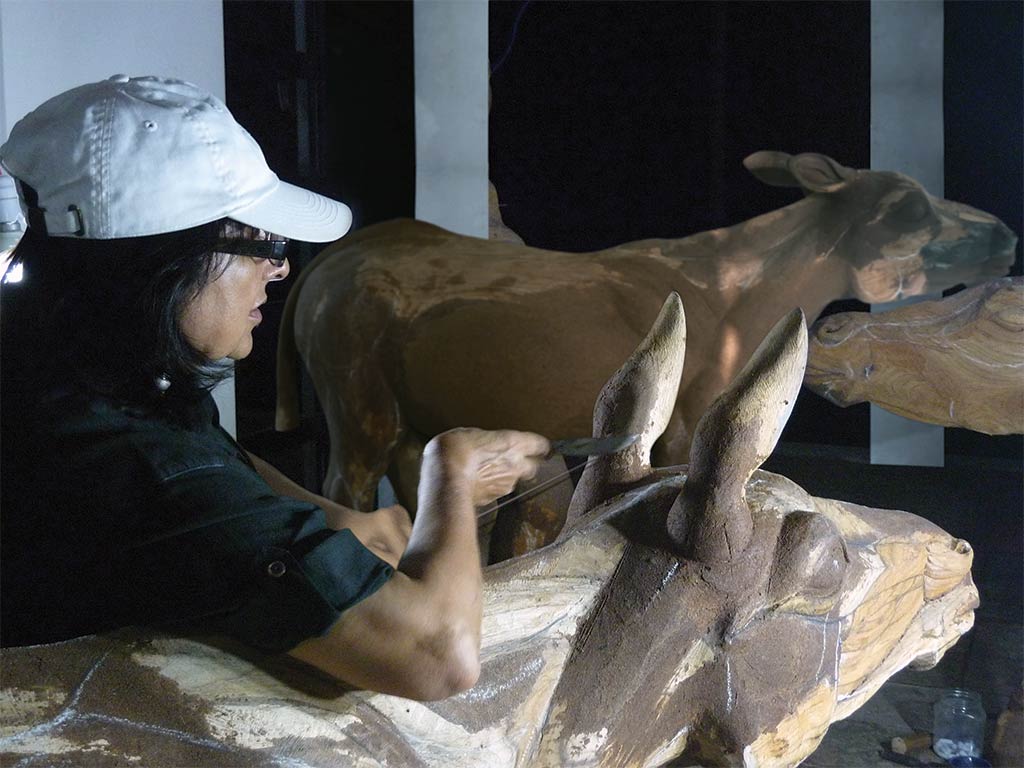

Navjot Altaf can easily become part of any list: Communist, Socialist, Feminist, Activist, Alarmist, Absolutist, and Anarchist… As you walk up the road and down to the lobby that leads to the lift that would take you to her flat on Nargis Dutt Road, which doubles up as her residence and studio and is close to Hindi film thespian Dilip Kumar’s house in south Mumbai’s tony Bandra area, you may wonder if she is a Capitalist. Those doubts would be dispelled the moment you step into her studio-cum-flat as it could belong to anybody who just carries the solemn wish to lead a peaceful life far away from the trials and tribulations that Navjot’s journey as an artist has gone through. This could be anybody’s life. But you would soon realise that Navjot is anything but a Conformist. That is the reason she has worked with all possible forms and mediums – from drawings to sculptures, from videos to sound.

She greets you with a smile as you enter her flat. This is not her main studio, but this is where she mostly works when she is not undertaking large-scale sculptural projects. For that she has another place that is ‘a bit far from the calm and cosy comfort of south Mumbai,’ she says with a smile that sits well on her short frame. As you walk past a closed door – which is where she conjures up an array of disturbing moving images along with her assistant – on the right of the corridor to her drawing room that doubles up as her dining room and study. It hits you, then, that her humble abode looks anything but the workplace of a veteran artist who has been throwing uncomfortable questions about our society at regular intervals over the years.

Everything in this space follows a straight line. The books are neatly stacked up on a rack next to the table in neat square rows. The chairs and the rest of the furniture are placed in an honest symmetry. Even the big refrigerator is not as intimidating as you first thought it would be as Navjot’s help opens it to get you a bottle of cold water. Everything falls into a line. It seems as if Navjot wants everything to be streamlined and work incredibly efficiently.

‘It was never like this, you know,’ she corrects any stray thoughts. ‘When I was in college, I studied both commercial art and painting. The applied art classes started at seven in the morning and went on till eleven; and the then the day college would begin. It was also a way of preparing yourself to survive in a city because you never thought that your work was going to sell. And at that time there was no such market. That was interesting, because in applied art they taught you to think about the bigger world and what impact your designs would have on the world; and in fine art you are taught to look inwards.’ And then you realize this irony that lies between these stark lines that frame the world inside her flat. ‘The line business was very interesting,’ she recollects. ‘In one class they would say that your lines are very soft, bring in some half tones and in another they would say your lines are very harsh!’

*

The walls in Navjot’s studio(s) don’t scream at you with a proud display of her collections. Navjot’s walls are as minimal and to the point as her videos, most of which grapple with inequalities of all kinds. ‘How to overcome the model of knowledge which is based on the premise of an inequality of intelligence and intellect, which could be based on the notion that the person without education is not without knowledge or the means to gather things together to form knowledge,’ she asks in another of her scribbles that she shares. ‘Intellectual emancipation is the verification of the equality of intelligence,’ she asserts.

It is only the next day that one gets to see what lies behind the closed doors of the room along the entrance passage of Navjot’s flat in Green Acres. This room again as nothing more than bare necessities, which is a couple of cupboards that don’t conceal much and has only two tables and a few chairs. Atop both the tables are Navjot’s desktops on which she edits her films. She then asks her editor to play her new work Soul Breath Wind. It is about the political, economic and ecological crises that have impacted the local communities in Chhattisgarh because of human activities.

We are immediately transported to the captivating environment of Barkuta, where intensive mining has made the lives of the local folk harrowing. Even after the film is over, Navjot keeps assuring me that there is more work to be done on the film and it is not complete. Yet, there is one sentence that underlines the entire import of Navjot’s latest work and her entire oeuvre, in fact. One of the suffering women when interviewed says in resignation: ‘…We have been exiled from our own land … This is the end, the soul of the soil has been removed. This is the end of life’.

Navjot sits silent for a minute, staring at the blank screen after the film is over. And then shakes herself and says, ‘I don’t think I am being very brutal about it. But I am just laying out things the way they are. And that’s what I’m thinking right now.’ Suddenly, the sparse studio makes a whole lot more sense. It is not bare. It is reverberating with her disturbing ideas. Apocalyptist!

Share