Meandering Precision, Attentive Chaos

A line might be intrinsic and obvious in our lives. When it emerges from the background into the spotlight, it becomes a fluid entity, surprising and delighting in the path it traces across the canvas of our minds. And when it disappears? We turn to art to join the dots.

Praveena Shivram

Prologue

That’s it. You hold the pencil down like this on the page and you move your hand, slowly, steadily, like this. Great!

Chapter 1: It’s a Draw

He was distraught. He was sure he had looked everywhere and that she had been there just a moment ago. He moved around in circles, trying to remember the last time he had seen her. How in the world was he supposed to move forward now? He picked up the phone and called Gagan Singh. Gagan Singh answered on the first ring.

He: She’s gone. Looks like a strikethrough.

Gagan Singh: How long has it been?

He: About 10 cms.

Gagan Singh: Hmmm. Do you think she has gone to the shoe store?

He: With that kind of length? I don’t think so.

Gagan Singh: Maybe it’s her visit day?

He: There were no suitcases, and no boy in a pugdi (though don’t tell anyone I said this. The word pugdi is causing a ban and a stir in some circles).

Gagan Singh: I know. We could hear the sounds.

He: What should I do, Gagan? She is somewhere between the drawing and the text, I am sure. You should know, right?

Gagan Singh: Well, some form of verbal conversation is always going on in the head. Maybe not at all times, but there is a conversation between words being formulated and what I am drawing. The delineation is usually where I find one telling the other that this is what I meant. So, the drawing telling the text and or the text speaking to the drawing.

What? He looks confused. He hangs up.

(If you want to know what happens next, go to Chapter 4. If you really don’t care, then continue.)

Chapter 2: I see You

Inside the cave, everything was dark. In the distance he could see a single flicker of light, moving slowly towards him. He could feel the rocky, solid texture of time seeping into his skin. He had been here before, he knew it. All around him, he suddenly felt the burst of Chinese calligraphy. And when he saw the face, he remembered. This was Lim Tze Peng’s domain, the wizard with the ink. Maybe, within these abstract forms and Peng’s wizened words, he would find his answer.

Lim Tze Peng: A good artwork, as I often emphasise, requires clean strokes and good ink work. Conceptualisation is important, as well as colour combination. Ultimately, it still falls back on your ink work and strokes. You improve through constant practice of calligraphy. You have to keep practicing, there are no shortcuts around it.

He knew Lim Tze Peng was telling him something, and this was his way – the messages were hidden, the clues inconspicuous, and the patterns evident only to those who were looking for something.

Lim Tze Peng: When working, you shouldn’t start painting immediately. You must first conceptualise your artwork. Only then every brush stroke will be decisive and purposeful. It will be a magical experience where the paint brush continuously interacts with the canvas, creating your art.

A faint glimmer of a path was coming towards him and he was about to pick up the phone to call Singh, when he heard Lim Tze Peng’s voice, his unhurried way of speaking, his measured words, yet again.

Lim Tze Peng: Painting is no doubt exhausting and challenging, but seeing my finished product fills me with a great sense of satisfaction and joy. I believe that when the day comes for one to leave the world, the legacy will be carried on by family and friends and people from all around the world. I feel one should not leave the world as a blank canvas.

A blank canvas. That was it! He knew what to do next but someone was going to have to help him. He picked up the phone and called the ‘someone’.

(If you want to know what happens next, go to Chapter 6. If you really don’t care, continue.)

Chapter 3: Cuts That Made It

There was knife. A hand was holding the knife. A body was holding the hand. A mind was holding the body. A face was looking at him and a mouth was talking to him, introducing himself as Kulu Ojha.

Kulu Ojha: When I use the knife to cut through layers of paper, I am more conscious about how to break the lines whether they are straight or curved, because there is no pre-planned image in my mind to do what I have to do, I just cut in a spontaneous way and use my sense of visualisation.

How was he going to survive this without her? He thought it was all just semantics, but apparently there was going to be some giving definition too. And apparently it was going to begin with him. He was going to be informing a new line of thought. Oh wait, wasn’t that what she had said to him before she disappeared? About this new place called Notepad created by Matt Kenyon where lines were more than what they seemed? He could picture her looking at him wearily from a distance, like she was already tired even before she had uttered the words and telling him what Kenyon had said.

Matt Kenyon: I was interested in the humble blank line because of the fact that it could be easily dismissed and overlooked by the viewer. To me this gesture was akin to the unacceptable treatment Iraqi civilians deaths were receiving in the American and coalition press. At first, Notepad was about smuggling these specially made pads of yellow legal paper into governmental archives. Each ruled line on the paper contained the details of individual Iraqi civilian deaths as micro-printed text. Part of the idea was that members of the government or their staff write on the “blank” sheets, the notepaper becomes part of our shared political history. At the end of the day – or the end of the administration – these sheets are gathered up and archived. The unacknowledged civilian body count data eventually makes its way into our nation’s history.

He had wondered aloud then if this was about if this was about his thickening, constricting circle of thought and if she wanted him to expand his ideas politically and she had just sighed and shoot her head. Now he was elsewhere. Darkness had replaced the sharp edge of the knife.

(If you want to know what happens next, go to Chapter 2. If you have already read chapter two because you couldn’t care less about this, ahem, extraordinary gimmicky structure, then please continue).

Chapter 4: Shapes and Forms

Inside the lab, the beakers were of all shapes and sizes. The walls were filled with what looked like cells joined in an intricate dance of static movement. He watched Timothy Hyunsoo Lee immersed in that world, his eyes focused as the cells flowed around him and he with them.

Without her, he knew he would lose himself here.

Timothy Hyunsoo Lee: I see each of my marks (not dots) as a cell – which metaphorically references the individual, but is also influenced by my background in neuroscience and my experiences researching in a neural stem cell laboratory. In making these paintings, I start off with one cell, without a predetermined composition, and gradually begin painting more and more cells – the network of these individual units organically forms into something larger and greater than what any single one of them could do alone. The resulting works are abstract, organic, and often disrupt our sense of space and time. The tension between the cells, locked into place but seemingly swimming in a fluid “meshwork” of white – the unpainted surface left behind – suggests that we are all connected to one another through a universal shared experience – that of living, being and passing.

What had Singh said about the drawing and the text? He started to understand that nature of dialogue here, in this lab, with these cells, and realised how he had ended up here.

He was, after all, a dot and yet not a dot, looking for his line. A form complete and yet incomplete. A seed with infinite potential for shape. He called Gagan again, because wasn’t it a phone company that said something about connecting people?

Gagan Singh: The connecting line is that the idea comes to me in the head as a sketchy form. So it’s not like the table had one round edge. It would be a visualisation of what is one of the corners was not round in the form of a visualisation. But then, there are no set rules. In the outside space, things around me can trigger an intervention. So the idea is to look for ideas to happen and sometimes forms lead to the idea, but there is no linearity here.

Ah. He knew where to find her.

(If you want to know what happens next, go to the next chapter because there is linearity here. Or go to Chapter 3. Because we lied.)

Chapter 5: In Repeat Mode

He didn’t believe in clones but when surrounded by an overwhelming number of them, belief became an insignificant rash. He seemed to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time. It was all becoming confusing, moving from plane to plane, canvas to canvas, mind to mind, in this search for salvation? redemption? perdition? repetition? All he really wanted was his line. If he could find a way to get to her, he could rest in peace. Amen.

Timothy Hyunsoo Lee: For me, repetition – and the act of counting – was a part of my life before painting, and before I first even laid a brush on a piece of paper. In repeating a certain action multiple times, over a long period of time, the automaticity of the action allows for the mind to wander and in the process, a mental sanctuary is born. The act of repeating has been something I used since childhood to deal with the extreme anxiety and panic attacks that I’ve had to deal with. There is something about exercising and claiming ownership of a deliberate and routine action that was able to subside the wave of negative thoughts that comes with losing control. I bring this action into my painting because I treat the process of painting as a form of meditation. One cell, one breath. The discipline and attention that my paintings require allows me to enter a mental limbo – an ethereal state of mind between reality and imagination – where I can confront various traumas of my life in a way that isn’t directly confrontational or intimidating.

Kulu Ojha: When I see a plan or a solid structure, I see the outer line of things. Then I see the intricate designs and how they fit into the structure, and I always try to break that repetition. In a single line I can repeat things but not in a repetitive way.

Matt Kenyon: For me, the everyday line of a single sheet of ruled paper is forever changed. I hope it is this way for those who have participated in the Notepad project. This is one of the powers of art. It can take the familiar everyday object and transform it and imbue it with new meanings. I think many of us have had our senses dulled by current political events. Art has the potential to shock us out of this state. It can, in an instant, reframe our relationship to news, politics and each other.

(If you want to know…. actually, does it matter? Please continue. If you want. Or don’t want. Or want to want. Or don’t want to want. Or want to don’t want to want.)

Chapter 6: It’s A Funny Business

Lim Tze Peng had already given him the answer to his quest. While his mind and soul had been wandering, he simply had to remain where he had always been – on that blank canvas. No line could dispel the allure of the blank canvas and as expected, she came, she saw, she laughed. Then more of them arrived and clustered around her, and as their hands started to snake into each other, I – the humble dot – held on to her – the limpid line – and joined in the laughter. And, of course, called Singh.

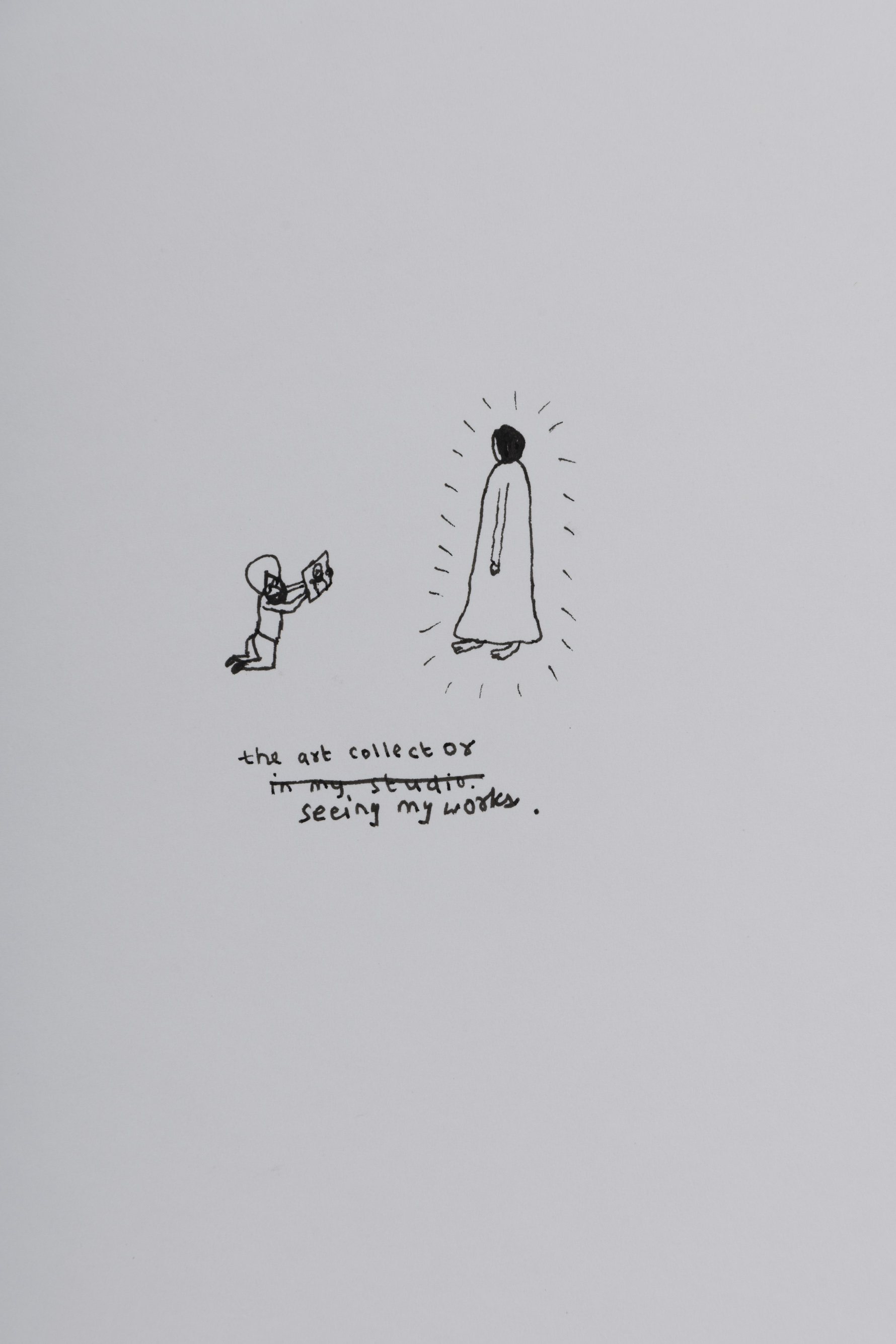

Gagan Singh: I’m sure humour would have different shades, tones, variations. The texture of the humour I have realised has come sometimes through extreme pain and suffering in life. And sometimes it is a feeling of playing with nonsense, irritation, to irritate others, from humour that we see around us to what we grew up hearing as humour to social media humour to what might make us laugh. So the texture of humour does change. What annoys me sometimes is people always taking my humour as cute. It gets on my cute nerves!

(If you want to know what happens next, go to Chapter 1. Ha! We already told you this was gimmicky, then why so surprised?)

Epilogue:

What’s in a line? That which we call the dot by any other name would walk just as fine.

Disclaimer:

With due apologies to the artists featured, who responded to a regular set of questions with a regular set of answers that have been put into an irregular set of stories. To know more about their work, visit:

Matt Kenyon: www.SWAMP.nu

Timothy Hyunsoo Lee: http://www.sabrinaamrani.com/the-gallery/artists/Timothy-Hyunsoo%20Lee/intro

Kulu Ojha: https://www.zoca-art.com

Lim Tze Peng: https://www.odetoart.com/?p=artist&a=126,Lim%20Tze%20Peng

Gagan Singh: http://chatterjeeandlal.com/artists/gagan-singh/

Share